CHAPTER 4: WITH THE AUSTRALIAN COMMUNITY

The following characteristics within this chapter relate to how well Australian development NGOs engage with the Australian community and stakeholders such as the government and the private sector. Relationships between development NGOs and the community are the lifeblood of organisations, bringing vital support through volunteering and donors. Similarly, stakeholder engagement with government and other partners helps to realise efficiencies in business and ensure that all needs are met.

Development NGOs also play an important role in advocating to the public and government in order to garner support and bring about change.

Highlights from the chapter

- The share of ACFID members that undertake advocacy has been steadily rising, increasing from 50% in 2011 to 59% in 2015. In 2015, advocacy was most common amongst large ACFID members, although 47% of small ACFID members still reported undertaking some form of advocacy.

- Australian development NGOs have worked on their own and together in a number of innovative campaigns. A significant example has been the Campaign for Australian Aid, which has had a steadily growing public support base, including a reasonable set of supporters that have been willing to take (usually internet-based) action.

- NGO organised trips to take parliamentarians to visit NGO projects in the field have been well attended by parliamentarians, and a collective NGO effort to educate parliamentarians in Canberra was able to reach over 60 parliamentarians or their staffers.

- At present only just over 20% of Australians believe that the government aid budget is too low. And political support for aid increases does not appear high in either major political party.

- It appears from ACNC data that over 70,000 Australians volunteered for development NGOs in 2015. About 30,000 of these volunteered via Rotary, 13,000 through other non-ACFID NGOs, and just over 26,000 through ACFID members.

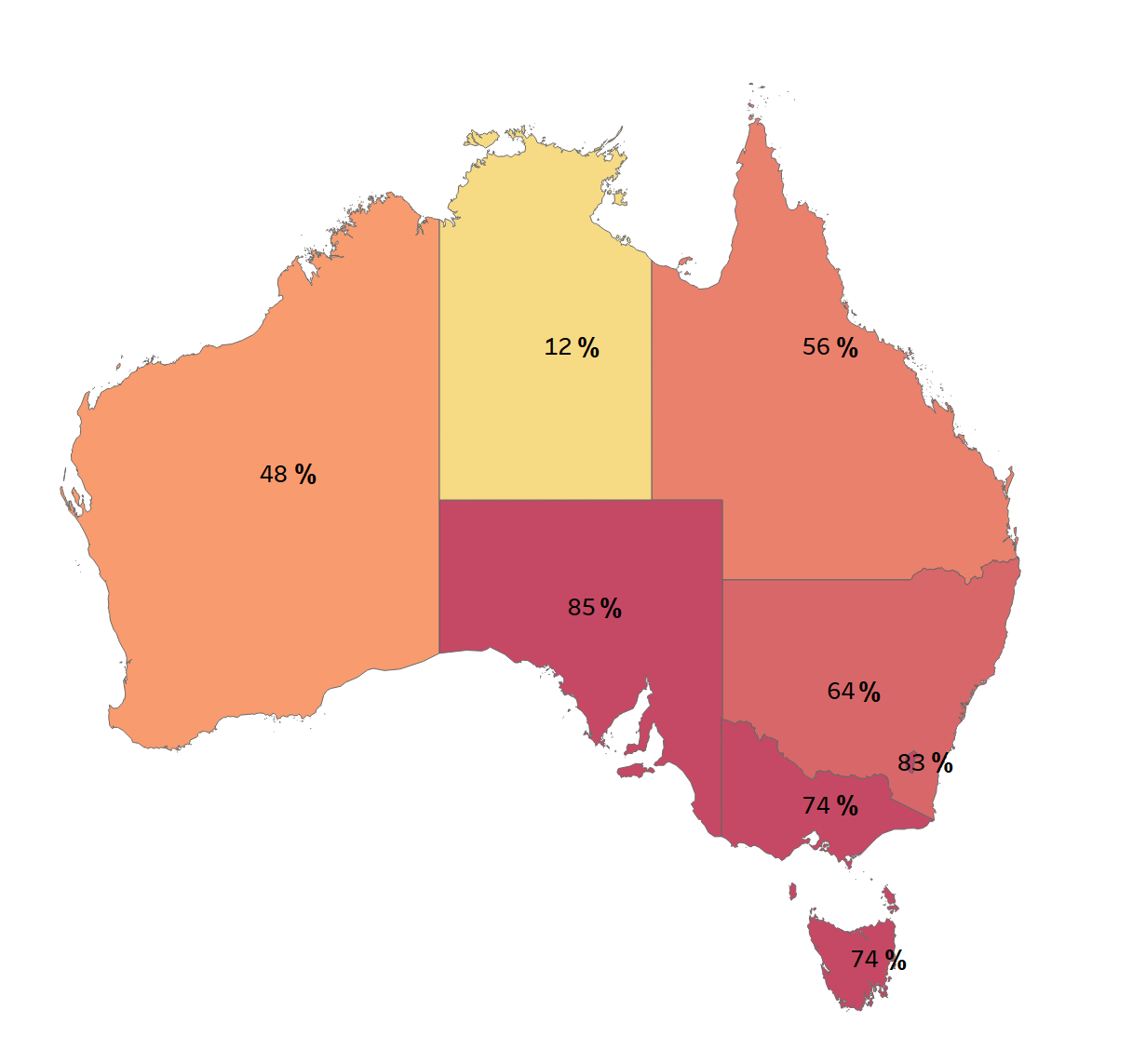

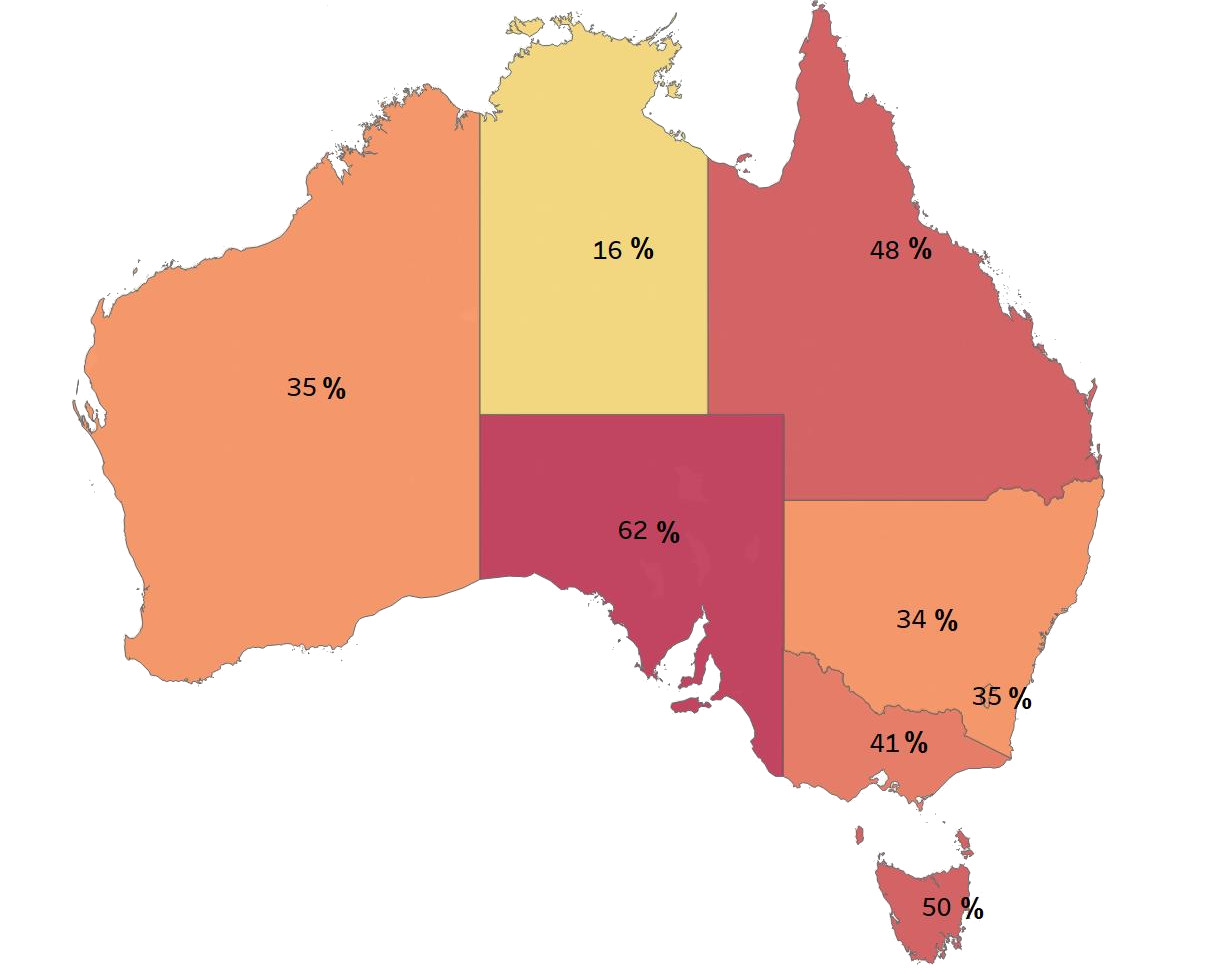

- Over 60% of Australia’s schools worked with at least one of ACFID’s larger members in 2015. As with donations, school support varied a lot between different states, ranging from 85% in South Australia to 12% in the Northern Territory.

- When surveyed, most Australians indicated that they are reasonably trusting of Australian development NGOs. Levels of trust in NGOs are almost identical to levels of trust in the government aid program. Trust in development NGOs is lower than trust in Australian peacekeepers, but higher than trust in Australian businesses that work in developing countries.

Indicator: Share of organisations undertaking advocacy

In a globalised world, the actions of developed countries impact on developing countries in many different ways. Donations to NGOs are not the only possible way that developed countries can help developing countries – their actions in other areas matter equally, if not more. Because of this, an important advocacy role exists for development NGOs. This does not mean that all of Australia’s development NGOs should be undertaking advocacy. Some may feel that their comparative advantage is in aid projects. This is fine for individual NGOs but it is not true for the sector as whole. It would be concerning if no Australian development NGOs were engaging in advocacy work. Figure 36 is derived from reporting that ACFID members undertake as part of their obligations under the ACFID Code of Conduct. It shows the percentage of ACFID members undertaking advocacy over time. As can be seen, over half of ACFID members are engaged in some form of advocacy and the trend is upwards.

Figure 36: Share of ACFID members engaging in advocacy

Figure 37 takes data from 2015 Code of Conduct reporting (the most recent that is available) and displays advocacy by organisation size group. As might be expected, larger NGOs are more likely to engage in advocacy, but nearly half of all small NGOs also undertake advocacy.

Figure 37: Advocacy by organisation size group

Indicator: Public engagement with campaigns

Figure 38 shows both the number of people signed up to the Campaign for Australian Aid and the number of people partaking in actions (usually online) when encouraged by the Campaign.

The Campaign for Australian Aid is a good example of a collaborative undertaking which involves a significant number of Australian development NGOs. The Campaign is not the only example of this type of collective NGO advocacy. Micah Australia, for example, is an Australian Christian movement which conducts similar work. Micah Australia has about 30,000 people signed up to its database, and as such is an important campaigning force in its own right. We have chosen to focus on the Campaign for Australian Aid in this instance, however, because they have a rich time series of data which they were able to share with us.

It is not our purpose here to evaluate the success or failure of the Campaign in its overall objectives. Rather, we are interested in what public engagement with the Campaign can tell us about the ability of Australia’s NGOs to interact with Australians when in campaigning mode.

Two clear facts emerge from the chart.

First, it is possible to elicit the interest of a considerable number of Australians in aid issues. 131,000 people is a very small share of Australia’s total population (0.54%) but as a potential campaigning force it is a substantial number of people. What is more, the trend on the chart continues to be upwards. Should resources continue to be devoted to this effort, it may well be possible to bring more Australians to the Campaign.

Second, while the number of people signed up with the Campaign shows that it is possible to raise some interest in aid issues, eliciting action is much harder. The greatest number of people taking a direct action in any month when prompted by the Campaign was 35,000 and usually, active engagement was less. (Note that in the chart below, in some months there were no calls to action.)

To date the Campaign has not succeeded in bringing increased aid budgets, although the ALP made a commitment to restore the $224M cut made by the Abbott Government in 2016. It has, however, operated during a time in which the government has been running deficits. It has also operated over a period when many political actors and many members of the public have not been sympathetic to the cause of aid. A counterfactual world without the Campaign’s efforts might have seen even worse aid outcomes. Most importantly, the Campaign’s work is evidence that a segment of the Australian public is willing to engage at least to some degree on aid-related matters.

Figure 38: Engagement with the Campaign for Australian Aid

new Chart(document.getElementById(“chartjs-40”),{“type”:”bar”,”data”:{“labels”:[“Feb-15″,”Mar-15″,”Apr-15″,”May-15″,”Jun-15″,”Jul-15″,”Aug-15″,”Sept-15″,”Oct-15″,”Nov-15″,”Dec-15″,”Jan-16″,”Feb-16″,”Mar-16″,”Apr-16″,”May-16″,”Jun-16″,”Jul-16″,”Aug-16″,”Sept-16″,”Oct-16″,”Nov-16″,”Dec-16″,”Jan-17″,”Feb-17″,”Mar-17″,”Apr-17″,”May-17″],”datasets”:[{“label”:”Actions”,”data”:[35000,32000,29000,15000,9960,2482,2482,2482,2482,10458,0,1719,5358,5358,9344,10453,12381,12381,1049,1049,12381,4027,9218,9218,33228,15000,9218,13909],”borderColor”:”#4C4C4C”,”backgroundColor”:”#4C4C4C”},{“label”:”Supporter base”,”data”:[1735,30000,41405,61452,62701,62701,63785,63785,63785,70441,70441,71495,71495,71495,74000,79315,96404,96404,97409,97409,97409,97409,105321,105321,122396,122396,122396,131245],”type”:”line”,”fill”:false,”borderColor”:”#98ADBB”}]},”options”:{“scales”:{“yAxes”:[{“ticks”:{“beginAtZero”:true},”scaleLabel”:{“display”:true,”labelString”:’Number of people’}}]}}});

Case study: Meeting with parliamentarians

In February 2017 a coalition of Australian development NGOs, ACFID, Micah Australia, the Campaign for Australian Aid and the Development Policy Centre sent teams to meet with Australian parliamentarians and their staff. The purpose of meetings was not explicitly advocacy. Teams were tasked with educating parliamentarians about aid and providing them with material from which they could learn more. In total, 30 people from 18 organisations participated. Invitations were sent to all Members of Parliament (MPs) and senators, although not all were available to meet. The NGO teams met with just over 60 parliamentarians (or in a minority of instances, with their staffers). Figure 39 shows the meeting breakdown by political party. There was more interest from parties on the political left, but a reasonable number of Coalition parliamentarians also met with teams, particularly given that it was sitting week, and ministers were not available to meet.

The February 2017 event was not the first time that aid’s supporters have met with parliamentarians. Organisations such as Micah Australia and the Oaktree Foundation undertake similar work. The February event serves as a good demonstration, however, of a collaborative endeavour, involving many NGOs.

Figure 39: Party composition of parliamentarians who met with teams

As part of the event, data was also gathered on parliamentarians’ views about aid. This has allowed the charting of where different parliamentarians sit on aid-related matters. Such assessments are subjective, and imperfect because of this. But they have the potential to improve NGOs’ understanding of the shifting tides of political support for aid. Figure 40 is based on teams’ assessments of how knowledgeable individual parliamentarians were of aid, and how supportive the parliamentarians were of aid. Each dot represents a parliamentarian. Blue dots are parliamentarians from the Coalition, red dots Labor, green Greens, and grey other parliamentarians.

The positive relationship between support and knowledge either stems from the ability of knowledge to increase support or it reflects the fact that few parliamentarians take time to become knowledgeable about matters they do not support. Most politicians who agreed to meet were at least somewhat supportive. Presumably this is because supporters are more likely to meet than avid opponents are.

Interestingly, although Labor politicians were more supportive of aid on average than Coalition parliamentarians, the divide was not completely clear cut; some Coalition parliamentarians came across as quite supportive, while there were also some comparatively unsupportive Labor politicians.

When we compared Vote Compass 26 data on public support for aid at the electorate level, and how supportive MPs were of aid when NGO teams met them, we found a positive relationship between public opinion and how supportive MPs were of aid. We also found that MPs from electorates where support for aid was higher tended to be more likely to agree to a meeting in the first place. This is not definitive evidence that public opinion affects politicians’ views, but it is a useful starting point in learning more about the relationship between public support for aid and political support for aid.

26 Vote Compass is a tool developed by political scientists for exploring how your views align with those of the candidates.https://votecompass.abc.net.au/

Figure 40: Parliamentarians’ knowledge of and support for aid

Case study: ACFID Child Rights CoP and ACCIR advocacy

The Child Rights Community of Practice (CR CoP) is an ACFID member-led and run working group. The overarching goal of the CR CoP is to promote the rights of children and child rights-based approaches to development within the Australian international development sector. The CR CoP currently has more than 60 members comprised of representatives from Australian development NGOs, government, and child protection consultants. For the past three years, one of the key objectives of the CR CoP, and the focus of one of four of its sub-groups has been advocating for the rights of children in overseas residential care institutions and this led to the development of a position paper titled Residential Care and Orphanages in International Development

In February 2017, a Federal Government Inquiry into Establishing a Modern Slavery Act in Australia commenced. Building on the previous paper, the Child Rights CoP produced a submission for the Inquiry. Furthermore, ACFID member, ACC International Relief (ACCIR), who act as the convenor for ACFID’s CR CoP sub-group on Residential Care and also co-chairs the ReThink Orphanages Network, co-produced with ACFID another supplementary submission to the Inquiry.In February 2017, a Federal Government Inquiry into Establishing a Modern Slavery Act in Australia commenced. Building on the previous paper, the Child Rights CoP produced a submission for the Inquiry. Furthermore, ACFID member, ACC International Relief (ACCIR), who act as the convenor for ACFID’s CR CoPsub,group on Residential Care and also co-chairs the ReThink Orphanages Network,

co-produced with ACFID another supplementary submission to the Inquiry.

Following these actions, many ACFID members reached out to the CR CoP for additional guidance and tools to initiate the shift away from such institutionalised models of care. Whilst this work is ongoing, it is a good example of the quick response and collaboration of development NGOs, all advocating towards a united cause.

Case study: Save the Children field visits

Since 2015, Save the Children has coordinated the Australian Aid and Parliament Project. This work is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and involves study tours in which Australian parliamentarians are taken to see aid projects in developing countries. Although the work is coordinated by Save the Children, there is a collaborative ethos and the projects of different NGOs are showcased in each visit.

Countries visited have been:

- Cambodia

- Jordan and Lebanon

- Myanmar

- PNG

- Solomon Islands

The purpose of the work is to help provide parliamentarians with a full understanding of role of Australian aid in the countries that receive it.

Thus far, 33 parliamentarians have taken part in the project. Five journalists have also participated

One risk of this type of undertaking is that participating politicians may tend to already be interested in and supportive of aid. It may be very hard to reach aid’s staunchest opponents. Save the Children has, however, attempted to reach out to parliamentarians who have a range of views on aid. Even so, most (although not all) participants were at least somewhat supportive of aid prior to going. Nevertheless, he field trips may still usefully strengthen existing support, and leave supportive politicians better able to argue the case for aid. Importantly, participation has been spread across both of the two major political parties. Figure 41, shows the party breakdown of participating parliamentarians. Labor is somewhat over-represented but the Coalition is well-represented.

Although it is too early for benefits in the form of increased or improved aid, the theory of change underpinning the work appears sound. There is some cross-country evidence that ministers in charge of aid programs give better aid when they are themselves more knowledgeable of aid (Fuchs & Richert 2017). And part of the sustained bipartisan increase in the aid budget in the United Kingdom appears to have been driven by individual politicians’ beliefs about aid.27 Similarly, high-level political support, often driven by a small number of politicians, appears to have played an important role in aid increases in Australia (Corbett 2017).

At this point the project has ongoing financial support. And Australian NGOs are active partners in the countries where the tours are conducted. However, like campaigning in Australia, the work needs to continue over the long term. Australian development NGOs should consider how their engagement can best be configured to ensure that this happens.

27 This is the finding of ongoing case-study research conducted by Ben Day, a researcher at the Australian National University.

Figure 41: Participation by party in parliamentary field visits

jQuery(window).load(function(){

if( typeof wpDataChartsCallbacks == ‘undefined’ ){ wpDataChartsCallbacks = {};

}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[39] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#98ADBB’,’#AD9610′,’#BF793A’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#98ADBB’,’#AD9610′,’#BF793A’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].backgroundColor =

[‘#D6DEE4′,’#EBE8DB’,’#F3E4D7′]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].borderColor =

[‘#D6DEE4′,’#EBE8DB’,’#F3E4D7′]

obj.options.options.scales.xAxes = [{stacked:true}]

obj.options.options.scales.yAxes =[{stacked:true, scaleLabel:{display:true,labelString: ‘Percentage of ACFID members’}}]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[40] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor = [‘#FF0000′,’#0070C0′,’#00B050′,’#BFBFBF’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor = [‘#FF0000′,’#0070C0′,’#00B050′,’#BFBFBF’]

}

});

One indicator of community support is the number and volume of donations that NGOs receive. This is discussed in an earlier chapter. There are many other useful measures of community engagement though. Available indicators are covered below.

Indicator: Volunteer engagement

One way that Australians show their support for development NGOs is through volunteering. Figure 42 is based on data from the ACNC 2016 dataset and compares the number of volunteers assisting ACFID NGOs with the number of volunteers assisting development NGOs that are not ACFID members. Surprisingly, given that ACFID members have greater revenue and employ many more staff, the total number of volunteers is higher for non-ACFID members than it is for ACFID members. However, this is primarily a product of more than 30,000 Rotary volunteers. If Rotary volunteers are excluded, ACFID members have nearly than twice as many volunteers as other NGOs.28

Figure 42: Volunteer numbers of ACFID members and other development NGOs

28 ACNC data presented a problem in that they do not separate volunteers engaged in domestic work from those who work on international projects. When working with ACFID members in the ACNC dataset we dealt with this issue by substituting ACNC data with ACFID data. However, for non-members, nothing could be done and volunteer numbers will be overstated to some extent because of this issue.

Figure 43 is based on data from the 2016 ACFID Statistical Survey. It compares the total number of volunteers in the sector with the total number of staff. It shows there are more than five times as many volunteers as employees amongst ACFID members taken as a whole.29

Figure 43: Volunteers and employees in ACFID members (2016)

However, composites for the sector as a whole are somewhat misleading. Different types of organisations have very different volunteer profiles and a small number of volunteer-heavy organisations contribute much of the sectoral total. Figure 44 addresses these issues. It draws on 2016 ACFID Statistical Survey data. It breaks organisations down into the different size groups and reports on the median NGO in each group, offering a sense of what the typical NGO in each size group looks like.

In the typical large development NGO there are about three times as many employees as volunteers. In the typical median NGO employees and volunteers are about equally balanced. In the typical small NGO there are nearly five times as many volunteers as staff.

29 Total volunteer numbers for ACFID members differ slightly from that in the previous chart. This is because the previous chart draws on ACNC data, whereas this chart comes from ACFID Statistical Survey data. A small number of NGOs provided different numbers of volunteers when responding to the two different surveys. Overall differences are small, however.

Figure 44: Volunteers and staff in the median NGO in each size group (2016)

Most volunteers contributing to the work of ACFID-member NGOs work in Australia. Figure 45 compares Australian-based volunteers with those based overseas (using ACFID member data from 2016). Most of the overseas volunteers in Figure 45 come from a small number of organisations. The typical organisation has no volunteers overseas.

Figure 45: Volunteers in Australia and overseas (2016)

Indicator: Number of schools supporting NGOs

Another form of community engagement is with schools. Figure 46 shows estimated school engagement by state. The number of schools engaging with NGOs comes from 2016 Electorate Snapshot data and the number of schools used to calculate the percentage comes from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data challenges mean that the figures are only approximations; however, they are accurate enough to provide a reasonable approximation of school engagement, and the extent to which it varies around the country.30

The chart shows excellent engagement in parts of the country. However, it also shows much variation. Engagement is particularly low in the Northern Territory

Figure 46: Percentage of schools engaging with development NGOs

30 In some instances, the same school may have supported more than one NGO. Where this has occurred, it may lead to overcounting of schools. Using information from a subset of organisations that provided school names, we estimate that for the country as a whole, the maximum possible magnitude of this effect is about 10 percentage points and is likely to be considerably less. Although the issue of double counting may have led to some overestimation in school participation, such overestimation is likely offset by the fact that the Electorate Snapshot survey only draws on data from 19 NGOs.

Indicator: Faith and community group engagement

Another form of public support and engagement comes through the support development that NGOs receive from faith groups and similar community groups. Data on the number of faith and community groups that supported NGOs in 2016 exists for large ACFID members, being available from ACFID’s Electorate Snapshot survey. While this data is not perfect, it provides reasonable estimates of the absolute numbers of organisations supporting the NGOs covered in the Electorate Snapshot survey. Unfortunately, it is much harder to estimate the number of faith and community groups in each state to allow for the calculation of the percentage of groups assisting NGOs. We have tried to do this using ACNC data on community organisations and churches. The results of our estimates can be seen in Figure 47 below. For now, the resulting numbers should be treated as loose approximations that are good enough to afford a sense of engagement in this form, and a sense of variation across the nation. As can be seen in the figure, variation between different states is high.

Figure 47: Percentage of faith and community groups engaging with development NGOs

Indicator: Survey data on support for aid

Another measure of the broader community environment that NGOs work within is general support for aid. Usually, public opinion surveys ask about support for government aid (we address survey evidence on views about NGOs in a subsequent section). Obviously, government aid and NGO work are not one and the same. However, information on support for government aid can provide a useful sense of the background climate that development NGOs work amongst. Not only do many NGOs receive some funding via the government aid program, but previous research has shown that there is a strong relationship, across different parts of Australia, between support for government aid and the propensity to donate to NGOs (Wood et al. 2016b).

Figure 48 shows results from a question included in Lowy Polls in 2015 and 2017 in which respondents (from a nationally representative sample) were told the current government aid budget and asked whether they thought that it was too much, the = right amount, or not enough (Oliver 2017).

In both surveys, most Australians think that the aid budget is ‘about right’. The second most frequent answer is ‘too much’.31 Those who think the aid budget is ‘not enough’ are a smaller minority in both polls. The share of respondents who think the budget is too small grew ever so slightly between 2015 and 2017; however, the magnitude of the change is so small that it may well reflect the survey sampling process rather than a real change in Australian attitudes. Even if the change is real, it is trivial.

The public sentiment captured in the Lowy survey does not fit with a public environment that is disastrous for the work of development NGOs. Yet it also does not speak of a public clamouring to see more money spent overseas. Australian NGOs could be working in a worse environment, but given public sentiment about Official Development Assistance (ODA), it is perhaps unsurprising that donations to NGOs have not outpaced the growth of the economy in recent years.

Figure 48: Australian public support for government aid

31 Similar surveying by the Development Policy Centre and for the Campaign for Australian Aid has produced similar results

Indicator: Surveyed public trust in development NGOs

Broad views about aid are an important element contributing to the environment that Australian development NGOs work in. However, more specific views about development NGOs themselves are also important. Trust in development NGOs is of particular interest. Even if an Australian supports aid, they are unlikely to contribute to the work of NGOs if they do not trust them. The data we have on trust comes from a 2017 public opinion survey commissioned by the Development Policy Centre.32 In the survey, questions were asked about the extent to which members of the public trusted the following types of Australian organisations:

- Australian development NGOs

- The Australian government’s aid program

- Australian army peacekeepers

- Australian businesses working in developing countries

Respondents were asked to respond making use of a 0–10 scale where 0 meant ‘do not trust at all’ and 10 indicated ‘trust them a lot’.

Figure 49 charts the average score given for each organisation type

Figure 49: Trust in NGOs and other organisation types

32 The survey was conducted by Essential Media with a representative sample of Australians (n=1026). The question asked was: ‘Thinking now about Australian organisations that work overseas, how much do you trust the following types of organisations to do the right thing all of the time?’ When we described each type of organisation, we took care to describe it in a way that the public would understand. We also took care to describe it in a neutral manner.

Peacekeepers were clearly the most trusted group, with NGOs and the government aid programs receiving almost identical scores. Trust was lowest in businesses working in developing countries. Although the results for NGOs and the government aid program were more or less identical, the difference between NGOs and businesses was statistically significant as was the different between NGOs and peacekeepers.

While a score of 6.02 for NGOs could be interpreted as a low level of trust, a more careful examination of the findings paints a more positive picture. Figure 50 shows the percentage of respondents who gave each score (from 0 to 10) for NGOs. There is a clear reluctance to place complete trust in NGOs. This can be seen by the low proportion of respondents who scored NGOs of either 9 or 10. However, the most common response is 8 out of 10. Nearly three times as many respondents gave responses above 5 as gave responses below five.

Figure 50: Detailed trust responses for NGOs

There were clear correlations between responses to the question about trust in NGOs and responses to questions about trust in the other organisations listed. People who were more trusting of NGOs tended to be more trusting of other organisations too. This was particularly the case with trust in NGOs and trust in the government aid program, but was also present between trust in NGOs and trust in peacekeepers and trust in businesses.

More detailed multiple regression analysis of the correlates of trust in NGOs showed that, controlling for the effects of other variables, academic education was clearly positively associated with trust in NGOs, while income was negatively associated with trust for NGOs. There was no difference in trust in NGOs between Coalition supporters and either Greens or Labor supporters. However, supporters of minor parties were less trusting, a relationship that appears to have been driven to an extent by the views of One Nation supporters.

At the same time that the Development Policy Centre was in the process of commissioning survey questions on trust in development NGOs, the ACNC released a report on a survey it had commissioned on NGO trust (Rutley & Stephens 2017). While most of this survey focused on domestic NGOs, a question was asked on international NGOs. On the basis of responses to this question, it appears that there is somewhat less trust in development NGOs than in NGOs conducting domestic work in Australia.

jQuery(window).load(function(){

if( typeof wpDataChartsCallbacks == ‘undefined’ ){ wpDataChartsCallbacks = {};

}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[42] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor = [‘#FF0000′,’#0070C0′,’#00B050′,’#BFBFBF’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor = [‘#FF0000′,’#0070C0′,’#00B050′,’#BFBFBF’]

}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[43] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#7F7F7F’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#7F7F7F’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].backgroundColor =

[‘#ADB9CA’,’#BF9000′]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].borderColor =

[‘#ADB9CA’,’#BF9000′]

obj.options.options.scales.xAxes = [{stacked:true}]

obj.options.options.scales.yAxes =[{stacked:true, scaleLabel:{display:true,labelString: ‘Number of volunteers 2016’}}]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[44] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’,’#98ADBB’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’, ‘#98ADBB’]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[45] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#CEC6A4′,’#CEC6A4′,’#CEC6A4’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#CEC6A4′,’#CEC6A4′,’#CEC6A4’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].backgroundColor =

[‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’,’#BF793A’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].borderColor =

[‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’,’#BF793A’]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[46] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#98ADBB’, ‘#595959’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#98ADBB’, ‘#595959’]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[47] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#AD9610′,’#AD9610’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#AD9610′,’#AD9610’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].backgroundColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].borderColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’]

obj.options.data.datasets[2].backgroundColor =

[‘#707070′,’#707070’]

obj.options.data.datasets[2].borderColor =

[‘#707070′,’#707070’]

obj.options.data.datasets[3].backgroundColor =

[‘#A6B1B7′,’#A6B1B7’]

obj.options.data.datasets[3].borderColor =

[‘#A6B1B7′,’#A6B1B7’]

obj.options.options.scales.xAxes = [{stacked:true}]

obj.options.options.scales.yAxes =[{stacked:true, scaleLabel:{display:true,labelString: ‘Percentage of Australians’}}]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[48] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#B7A02F’, ‘#B7A02F’,’#B7A02F’, ‘#B7A02F’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#B7A02F’, ‘#B7A02F’,’#B7A02F’, ‘#B7A02F’]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[49] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#CEC6A4’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#BF793A’,’#BF793A’, ‘#CEC6A4’]}

});

Providing funding is only one of a number of ways that the Australian government can help Australian development NGOs undertake their work. Another crucial contributing factor is that a regulatory regime serves the public interest while at the same time not unnecessarily encumbering NGOs.

Indicator: Agencies with DGR and OAGDS status, and ANCP-funded agencies

One important means through which the government can aid the work of development NGOs is through making it possible for them to obtain a status under which members of the public who provide them with donations can claim tax deductions. In Australia this comes through the Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) status.

In 2015 and 2016 ACFID collected data on whether its members have DGR status. Data from 2016 year indicates that almost all ACFID members have DGR status. In 2016 100% of large and medium organisations did, and only two small organisations did not.33

One specially tailored means for international development NGOs to obtain DGR status is via the Overseas Aid Gift Deduction Scheme (OAGDS). Figure 51 shows, by size group,the percentage of ACFID members who are registered via OAGDS. For most larger and medium sized NGOs, OAGDS has proven an effective mechanism for attaining DGR. This is less often the case for smaller NGOs. Why smaller NGOs are less well served by OAGDS is unclear.

Figure 51: OAGDs registrations (2016)

33 In instances where organisations stated that they did not have DGR status we double checked against the official ATO list of organisations with DGR status. These two organisations were also absent from that list.

The Australian government’s central funding mechanism for NGOs is the ANCP. Its funding substantially augments money that NGOs obtain through public donations. It also adds useful additional layers of quality assurance including monitoring and evaluation requirements. The share of ACFID-member NGOs able to access the ANCP is shown in Figure 52. Most large NGOs and the majority of medium sized NGOs have been able to access the ANCP. However, only a minority of smaller NGOs have been able to. Under-representation of smaller organisations is not surprising. The criteria for ANCP accreditation are organisationally demanding. Moreover, because it is a matched fund reflecting public donations, the absolute benefits for smaller organisations from accreditation are less.34

Figure 52: ANCP registration over time

34 Note that the categories used here were in place up until 2016. They are now in the process of changing.

Indicator: The state of the political, legal and policy environment

The legal, political and policy environment that ACFID members and International Non-Government Organisation (INGOs) operate in has been undergoing some changes in the past few years, particularly since the change of Government in 2013. A change of government will understandably come with a change in political ideologies and priorities. This has been most evident in the macro-policy guiding Australia’s aid program. In 2013 ACFID co-designed and co-launched DFAT’s Civil Society Engagement Framework, and in the following year that had been replaced by the New Aid Paradigm, and 2015 saw ACFID launching the NGO Engagement Framework with DFAT.

For the legal and policy environment, the dominant feature in the past few years has been the ongoing uncertainty around the statutory regulator – the ACNC. While the Turnbull Coalition government confirmed that the Regulator will stay (in contrast to the Abbott Coalition government), the scheduled review of the ACNC in 2018 could shift the purpose and functioning of the regulator significantly. Depending on what positions are taken, this could have an impact on INGOs’ reporting and regulation.

Charities also fall under other legal and policy regulations in relation to their finances (Treasury and Austrac), lobbying (Attorney-General) and campaigning work (Australian Electoral Commission), and there have been shifts in these jurisdictions too. Most notable were the changes to the OAGDS register, and the moving of all DGR registers to the ACNC, the slated changes to the lobbying register and the introduction of a Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme, and the proposed Electoral Act changes which may constrain the advocacy work of charities and curtail their receipt of international philanthropy.

jQuery(window).load(function(){

if( typeof wpDataChartsCallbacks == ‘undefined’ ){ wpDataChartsCallbacks = {};

}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[50] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#98ADBB’,’#AD9610′,’#BF793A’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#98ADBB’, ‘#AD9610’, ‘#BF793A’]}

wpDataChartsCallbacks[51] = function(obj){

obj.options.data.datasets[3].backgroundColor =

[‘#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’]

obj.options.data.datasets[3].borderColor =

[‘#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’,’#98ADBB’]

obj.options.data.datasets[2].backgroundColor =

[‘#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’]

obj.options.data.datasets[2].borderColor =

[‘#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’,’#7F7F7F’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].backgroundColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’]

obj.options.data.datasets[1].borderColor =

[‘#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’,’#4C4C4C’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].backgroundColor =

[‘#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610’]

obj.options.data.datasets[0].borderColor =

[‘#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610′,’#AD9610’]

obj.options.options.scales.xAxes = [{stacked:true}]

obj.options.options.scales.yAxes =[{stacked:true, scaleLabel:{display:true,labelString: ‘Percentage of ACFID members’}}]}

});